Billie Hanson-Dupree

Black Gold, Black Harvest

I met Merian (Mae) Minor Givens about fifteen years ago at Church of the Good Shepherd in Oakland. She welcomed Sunday morning visitors, and after the welcome, she added a poem or scripture of encouragement to the parishioners.

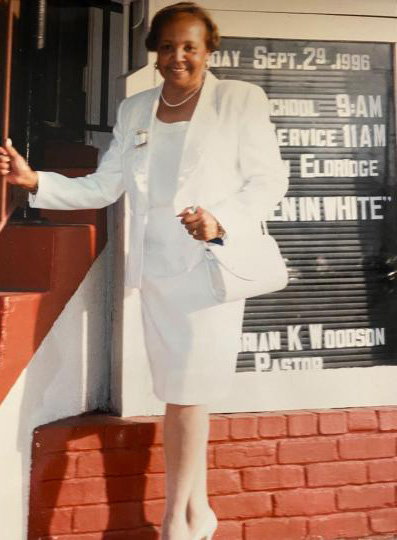

At that time Mae was about 80 years old and, as they say, “sharp as a tack.” She wore a lovely white suit with a matching purse and high -not stilettos- but high white heels. There’s a saying “Age ain’t nothing but a number.” Today at 95, Mae can still style and profile with the best of them.

When I think of harvest, I often think about harvesting vegetables from a garden or fruit from a tree. The story of Mae Givens is one of acquiring a harvest, but not only from her garden. She also harvested knowledge and an indominable spirit from her mother Georgie who Mae characterized as “a strong woman and she wasn’t afraid of anything. She’d speak up.” The same can be said of Mae.

Mae grew up in South Baton Rouge, a stone’s throw from LSU on one side and the Mississippi River on the other. Out of necessity Mae was a tomboy, there were few girls who lived near her home on West McKinley Street in Baton Rouge. Mae played tackle football, marbles, and Bunkie with her brother William and the neighborhood boys. At home Mae helped with the cooking, cleaning and cared for a small family garden. And flowers. Her mother, Georgie, loved flowers and beautiful blooms were always in their front yard. She recalls “We had a huge pear tree and every year there would be pears and pears. We’d pick them by the sacks and she (Mother) would sell them.” They also had two or three fig trees and shared an alligator pear tree with neighbors, “Mother had a hen house where she had chickens and we would go out and get the eggs. Those game hens were navy blue and they were mean.”

Mae attended a small church a few blocks from her home where was baptized at the age of 12. Mae’s maternal uncle was the minister, and her paternal uncle was a Deacon “so I had to go to church. What else was there to do?”

She told me, “Some black churches would have baptism in the Mississippi. You could almost walk from my house to the River… the buses would pass my house and there would be maybe four or five busloads taking the candidates and the members down to be baptized in the river and they’d be singing and clapping their hands. My brother and I would run to the front yard and watch them go by.” She laughed.

During summers while her mother worked, she and her brother William were sent to stay with her grandparents, the Lacours in Batchelor Louisiana. Mae loved it. She and her brother were too young to work so they watched the adults in the fields. Mae told me “Everything you wanted to eat was right in the yard. If you didn’t have it the neighbor had.” Her grandparents had a smokehouse where they smoked chickens, bacon and ham. She said that after the hog slaughter they used everything from the hog-from the rooter to the tooter. They even used the blood to make blood sausage.

Mae recalled, “when it was time to go to church we’d go in the wagon, nobody had cars. They would take baskets of food and after church on certain occasions you would sit out under the trees and eat. The cemetery was right on the grounds where the church was.”

Mae attended a private preschool which served the Blundon Colored Orphanage Home because her mother worked for the home. She shook her head. “When we went to Reddy Street Elementary School, they called us Blunden rats and those kids would tease us all the time because we went to the school at the orphanage.” When her brother beat up one of the tormentors, they were left alone.

She told me about the principal who was, “A little lady who reminded me of Judge Judy.” We laughed. “She would come out there and she’d ring this bell when it was time for you to come in. You had to be in the line, a straight line and if you said something, she had a belt like those shaving belts that you sharpen your razor with. You would go to her office, and she would whip the kids.” She shook her head and added, “They can’t do that today.”

Mae took pleasure in music and dancing. She learned to play the piano from a teacher who would rap her on the knuckles if she hadn’t practiced. At home she played the blues and said “I would play the radio and record player so loud mother would come and make me turn it down.”

Her brother asked their mother to make Mae teach him how to dance, but Mae said, “he’d move so slow I said, oh, William you got to move faster, so he never really learned how.”

The Great Migration holds as many stories as families who left the south. Entire families packed up and moved, some sent one family member to test the temperature. After attending Southern University in Baton Rouge for two- and one-half years Mae knew she wanted something different.

With her mother’s blessing, she took the train from Baton Rouge to Oakland in 1948. The segregated train was filled with African American soldiers who had priority seating, although she never had to give up her seat. As a young woman traveling alone, Mae said she felt afraid at times, but the men were nice to her. When I asked her about eating on the train, she said, “My mother had packed fried chicken for me in a small box, but I would only take a few bites at a time, embarrassed to eat in front of all those men.” She shook her head.

When she arrived at the Sixteenth Street Train Station in Oakland, she was greeted by James Givens, a longtime friend from Baton Rouge whose parents had moved to Oakland in 1941. James whisked to her aunt and uncle’s house which still stands at the corner of California and 63rd Street in Berkeley. Her uncle, Gus Mann, was also her godfather and “You had to walk the straight line with him. He was very strict. Because of the size of the family, there were six of us, every Sunday we knew we were going to have the same recipe of chicken mixed with spaghetti and spaghetti sauce. He (Uncle Gus) could really cook.”

She told me about some of the young people she met when she first arrived. “They always thought I was kind of country because I used to keep my legs oiled with Vaseline and wore socks and I dressed (up)a lot because my mother was a seamstress and made everything I wore. She made my coats, dresses, suits and I always thought I looked very nice.” It’s a testament to Mae’s strong spirit, that she did not let the comments deter her from dressing up to this day.

In 1949 the Southern University Jaguars played football against the San Francisco State Gaters and Southern trounced them-30 to 0. She vividly remembers riding around Berkeley in a convertible on the way to the game on a rainy, muddy day. That evening she returned to San Francisco for the Southern dance where she was crowned Miss Southern because of her connection to the University.

Mae attended Merritt College for a while, then gained employment at the photography studio of E. F. Joseph, the first professional African American photographer in the Bay Area. Subsequently, Mae worked at Joseph Magnin in Oakland as a tea girl (serving tea to women who shopped for ribbon knits) and moved up until she reached the position of credit manager.

In 1950, Mae married her childhood friend, James Givens who had lived only a few blocks away from her in Baton Rouge.

Mae smiles when she shared that she and James loved to dance. They were so good, that they often took over the dance floor. When I asked her where they went to have a good time she told me about places in West Oakland such as Esther’s and Slim Jenkin’s clubs. They ate bar-be-que at Earl’s. James and his friends played pool at Dallas’ Pool Hall. Except for the drug store, Mae recalled that most establishments in West Oakland were owned by blacks at that time. One of her favorite memories was watching the cross-dresser Jean LeRoux entertaining them at the Clef Club wearing a feather skirt and using feather fans. Standing at her walker, Mae says, “I miss dancing, but when a song comes on that I like, I still can move a little.” She demonstrates with a shake of her shoulders, and a giggle.

Mae went to work at the University of California in 1960 and worked there for 28 years. She retired in 1988. She started as a clerk and advanced to administrative assistant in the office of the president.

In Mae’s words, “I just got tired of, I guess of being told what to do or something and James had a good job. He was a longshoreman. And I just gave it up and I haven’t worked since.”

Although Mae stopped working at the University, she continued to flex her creative muscles. Using the skills she harvested from her mother and aunt she continued sewing, making gift baskets, ornaments and mantle pieces every Christmas. Her daughter Jan would bake pies and they would sell them and the crafts out of their home.

All her life, Mae loved to take photographs. Many of the photographs in this slide show her story are examples of Mae’s skills.

Mae’s mother nurtured flowers in Baton Rouge, and you can’t help but notice the flowers and plants in the yard of Mae’s Acton Street home. A Sweetheart Rose bush and geraniums that she brought from her childhood home in Baton Rouge bloom beside her house. A Meyer lemon tree and a large pyracantha shrub flourish in her backyard. Her planter garden which usually yields tomatoes, collard greens, squash, and string beans sits dormant. She said she hates that she can’t get outside as much to garden anymore. She nods toward her walker.

Mae’ active involvement in church after she moved to Berkeley was a harvest of her church upbringing in Baton Rouge. She attended Beth Eden Baptist Church under Reverend Hubbard for seven years and settled at Church of the Good Shepherd in 1957 under the leadership of Reverend Henry Mitchell. She served in many capacities, including Greeter, Sunday School Superintendent, Chair of the Board of Christian Education, Secretary of the Sunday School and as a choir member-Mae sings too! When I asked Mae what was her most fulfilling accomplishment at Church of the Good Shepherd she sat up taller and smiled. “I created the African American Celebration Festival.”

I had the opportunity to attend this Festival several times and I understand the breath of Mae’s accomplishment. Too large for the Church of the Good Shepherd, the Celebration was first held at Taylor Memorial Church then became so popular that it was held at Lake Merritt United Methodist Church. The Celebration included a fashion show, delicious soul food, vendors and a raffle. This festival became an annual event that church members and the community anticipated with excitement.

Mae finished our interview with these words, “I think I’ve had a beautiful life.”