By Rashida Chase

Growing up I knew that my dad was from Louisiana, and I remember visiting family on a farm there when I was in sixth grade, but there was always a disconnection between our family in Louisiana and those of us who were in California. I am a child of Oakland through and through, mostly because of the deep love that my father has for the place that became his home. Him becoming an athlete and being relatively well known in pockets of Oakland trickled down and colored a lot of how I saw and experienced the city.

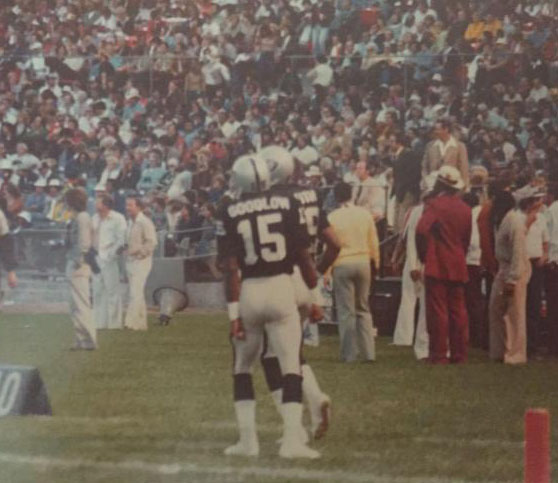

When I was 10, around the same age my dad came to California, I just knew he was famous because everywhere we went he was mistaken for popular celebrities of the time. People of all persuasions thought he was a variety of celebs, usually either Tim Brown the football player, Eddie Murphy, or Wesley Snipes. I remember as a little girl, being out with him at various events or stores, just anywhere in Oakland, and random men his age would spot him from across the street. They would either stare and try to figure out whether or not it was him, or they would yell his last name, sometimes from across or down the street, “Goodlow!”, to confirm it was him. Then they would come barreling over to us and begin to tell me and my sister about my father’s athletic accomplishments in GREAT detail. It was always so fascinating to see how much these men remembered about the games he played in, specific plays he ran, and how many points he got and touchdowns he scored, all those years after the fact.

I’ve always wondered how much he remembered growing up in Louisiana, and as much as my father and I talk about life and what’s going on now, we never really talked about his experience of coming from Louisiana to California as a young person. So, we started from the beginning.

On June 7th, 1954, driving on the highway between Rayville and Shreveport, Louisiana, my grandmother, Corine, was in active labor. At some point between Monroe and Shreveport, she realized that she was not going to make it to the hospital, and they turned back to try and get to the hospital in Monroe, but my dad had other plans. He was born in the car, on the side of the road. My father has never been one to wait for the “right time”, and his birth was the first example of him making it the right time, whether it felt that way or not. This personality trait would benefit him in many ways and change the trajectory of his life.

The first house he remembers living in was in Shreveport, a little white house with a white picket fence when he was three or four years old. When I asked more about the house, he said it was a vague memory, and that his family had moved around a lot because of his stepfather, Robert. “He didn’t like to pay his bills, so we were always moving to a new place,” he told me, but he remembers the house where he spent most of his time in Louisiana. It was a shotgun house that had a few stairs in the front, and was on a cul-de-sac with a dirt road. His aunt, Luverta, who they called Aunt Red, lived down the street. My dad and his older brother, Charles, used to play with their cousins at Aunt Red’s every day. He talked about the street being on a hill, and when they would play football. If you were on offense you had to run up the hill, so they got their early sports conditioning from playing with cousins and other kids who lived on the block. Their home life was very tumultuous and daily they witnessed domestic violence between my grandmother and her husband Robert.

The second child was born to Corine Goodlow and Earnest Mock. My dad and his older brother Charles (Edward) were ostracized and abused by their stepfather, who fathered four children with my grandmother, Thelma (Pookie), Robert (Lil Brother), Lester, and Daphne (Daffy). The abuse my grandmother suffered at Robert’s hands was the genesis of the move to California.

My dad recalls a day when Robert and my grandmother had been fighting while the kids were supposed to be sleeping and my uncle Charles went out to defend his mother. Robert chased after him and my uncle took off, leaving my dad afraid that Robert would come and hurt him. He said that Robert called him into his bedroom and asked, “Are you mad at me?” My dad said “no” and was allowed to go back to bed. When he woke up the next day, he found out that his brother had run down to Aunt Red’s house, and my grandmother had made a pact with her sister that my uncle could stay there until she figured out what she was going to do. My dad, upset at being separated from his brother, started plotting to hurt Robert for what he had been doing to him, his brother, and mother.

One day soon after, he was outside playing and the neighborhood kids told him that he should go home and check on his mother because it sounded like Robert was fighting her again. He describes running to the house and hearing lots of commotion, coming to the door where he saw them fighting, and just like in the movies, watching them freeze as soon as they saw him. They froze, looked at him, and Robert told my dad to go back outside. He didn’t. He stayed right there, and as Robert started advancing toward him, he backed up, being mindful of the front stairs, and stayed just far enough away that Robert wouldn’t be able to get to him. He said all of a sudden he remembered that there were loose bricks near the stairs, and it put him on high alert. Sure enough, Robert grabbed a brick and threw it right at his head, and had he not been paying attention, he would have been hit square in the forehead. My grandmother saw the look in my father’s eyes, and she knew that Robert’s time on earth would be coming to an end quickly, and she had to get her son away. So the next day, they were on a bus to another aunt’s house, Aunt Essie Mae.

According to my dad, Aunt Essie Mae was a mean old lady who was a sharecropper and put all children who were old enough out in the field to work, picking cotton. My dad didn’t want to pick cotton and was adamant that he wouldn’t do it. So the adults called him lazy and said he’d never work or make anything of himself. They tried to trick him into working and thought giving him a new bag would make him excited to work; he just thought it was funny and decided that he would prove to them that he could do it. One day he went out to the field with everyone else, took the new bag and filled it to the brim with cotton, much to the surprise of all the adults, who praised his work effort. All of a sudden he became a “good kid” in their eyes. He never picked cotton again.

He later moved to live with his Aunt Corine, my grandmother’s namesake, and said it was like night and day, she was the exact opposite of her sister Essie Mae. She was the sweetest woman he had met besides his mother, and was loving, supportive, and good to him. While he was living with Aunt Corine, his mother and brother Charles had moved to California, and he was livid. “Why did you leave me here? What did I do?” He recounted the feelings he was experiencing when they left. My grandmother felt bad for leaving him and would send clothes that had California or palm trees on the tags, and people would tell him that they heard the streets of California were lined with beautiful palm trees and paved in gold. After a year or so of living with Aunt Corine, the day finally came that his cousin came to get them to drive to California, and they began the journey west.

Before coming to California, my dad had only seen white people two or three times, and had never seen Latino or Asian people. His first encounter with white people happened at a very tender age and was forever etched in his memory. Transporting back to Louisiana, he was five years old, hanging with his older brother, my Uncle Charles who was 8 at the time, our cousin Junior Flakes, 12 or 13, and Donny, who was 8 and Charles’s best friend. They were outside in the front yard on the porch, playing in front of Aunt Red’s house four doors down from where my dad and uncle lived, and all of a sudden they saw a 1954 Ford Customline, a car with dark green top and lighter green body, that came to a screeching halt not too far from them. Four white teenage boys jumped out of the car and yelled repeatedly, “You fuckin’ niggers!”. They threw water balloons at my dad, his brother, cousin, and friend. The balloons didn’t come anywhere close to them, so they just stood there and looked at them, confused. They got back in their car and took off. Everyone seemed unphased, but my dad, the youngest of the group, had never heard the word before. He repeatedly asked them, “What is a nigger? Why are they calling us that?” His brother and cousin told him to let it go and leave it alone, “forget about it, don’t even think about that,” they said.

Dad would go on to play at Cal State Northridge but would leave there before fulfilling his eligibility requirements because of issues with the coaches. After leaving CSU Northridge, he went to Seattle to train for the triple jump in the Olympics and stayed with my Aunt Elsie’s family. Two of her daughters told him that a new football team, the Seahawks, was recruiting players and that he should go out for the team. He went to the try outs; the team loved him and wanted to sign him. After talking to him about his college experience, they realized, to their dismay and my dad’s, that they couldn’t sign him. Without eligibility from Northridge to qualify for the team, Dad had to give up on football again.

When he came back to California, he ran into an old friend named Joe Abrams he used to play against in high school. Joe told him about a semi pro team in Fairfield that was basically a feeder for NFL teams and asked Dad to join. He did, played well, and was encouraged by this same friend to try out for the Raiders. He gets the number to the player personnel officer, Ron Wolf, calls him and says, “Hello. I’m Allen Goodlow. I understand you guys are gonna be having some trials,” and told him that he should be on the team. Astounded, Ron asked him if he knew who was on the team and asked what made him think he was good enough to play in the NFL.

My dad replied “Yes!” and affirmed that he knew who was on the team by naming players like Raymond Chester, Cliff Branch, and Jack Tatum. He said he was good enough because he played better than everybody the Raiders currently had in his position on the team. Ron laughed and said, “Wow, I’ve never heard anybody say anything like that before,” and told him to come to the trials. He shows up, runs a 4.35 (which is VERY fast) in the 40-yard dash, and caught eight or nine passes, four of which were touchdowns, and blows everyone away. He was signed to the practice team and had to fight for his position from January to June to earn his spot on the team. He beat out all of the other players and made it to June. By that time, he was nursing injuries that made him question whether or not he wanted to continue his football career. At the time, my mother was pregnant with me, and he was grappling with the decision of whether or not to play pro ball and risk further injury, or to be there for his new daughter.

After working hard all those years in high school, college, playing semi-pro, almost joining the Seahawks, and talking his way into a tryout with his home team, he made one of the biggest decisions of his life. He chose me.

I asked my dad why he chose to stay home and be with me instead of pursuing his longtime goal of being in the league. He said he gave up the possibility of earning millions and being famous because he wanted to be there for me in the ways that his father wasn’t. He said that he wanted to be present for me, and that he made the best choice. Imagine that. Your dad giving up riches and fame just to be able to spend time with you.

While we could have lived a very different life had he stayed in the NFL, I am eternally grateful that he made the choice he did. All of the work I do for my community today, and the ways that I love on my children is with his sacrifice in mind, and wanting to continue the legacy he started being born on the side of the road. By believing in ourselves, creating our own opportunities, and making it the right time, whether it feels that way or not.

Storyteller Bio:

An Oakland native, vocalist, and culture and wellness advocate, Rashida Chase has always sought ways to integrate instead of compartmentalize her seemingly disparate passions, and believes that music is a healing force and a unifier of people. She recognizes the power of inspiration and creativity that music holds and strives to create experiences that soothe, heal, and inspire her audiences to tap into that power and realize their full selves.

By Rashida Chase

An Oakland native, vocalist, and culture and wellness advocate, Rashida Chase has always sought ways to integrate instead of compartmentalize her seemingly disparate passions, and believes that music is a healing force and a unifier of people. She recognizes the power of inspiration and creativity that music holds and strives to create experiences that soothe, heal, and inspire her audiences to tap into that power and realize their full selves.

BIO FOR ALLEN GOODLOW

Allen Goodlow was born in 1954 in Louisiana, on the road between Rayville and Shreveport. When he was ten he moved to Oakland with his mother and five siblings. He attended Oakland public schools and was a star athlete at both Oakland High and Laney, excelling in basketball, football and track. Allen also played on the Raiders practice squad for a season before leaving football to become a new father. He has six children and ten grandchildren. He is a fitness trainer and works primarily with clients 55 and over.