By Wanda Sabir

I

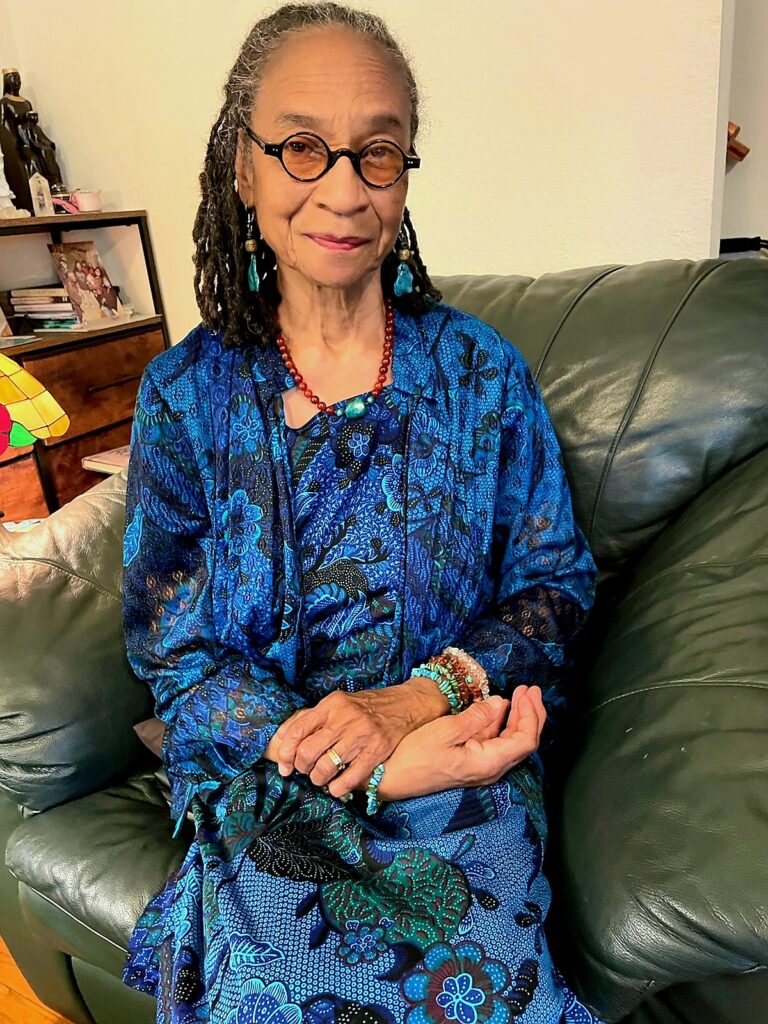

Sister Lola Mae is wearing gemstones, amber and turquoise. She works magic, stone stirred pots sing music as ancestors settle in for the spin. We wrap history on spools between us. Her 75th birthday just a little over a month past, February 4, this warrior wom(b)an holds in her person a people and a nation. And unlike many other wom(b)an, she knows her power.

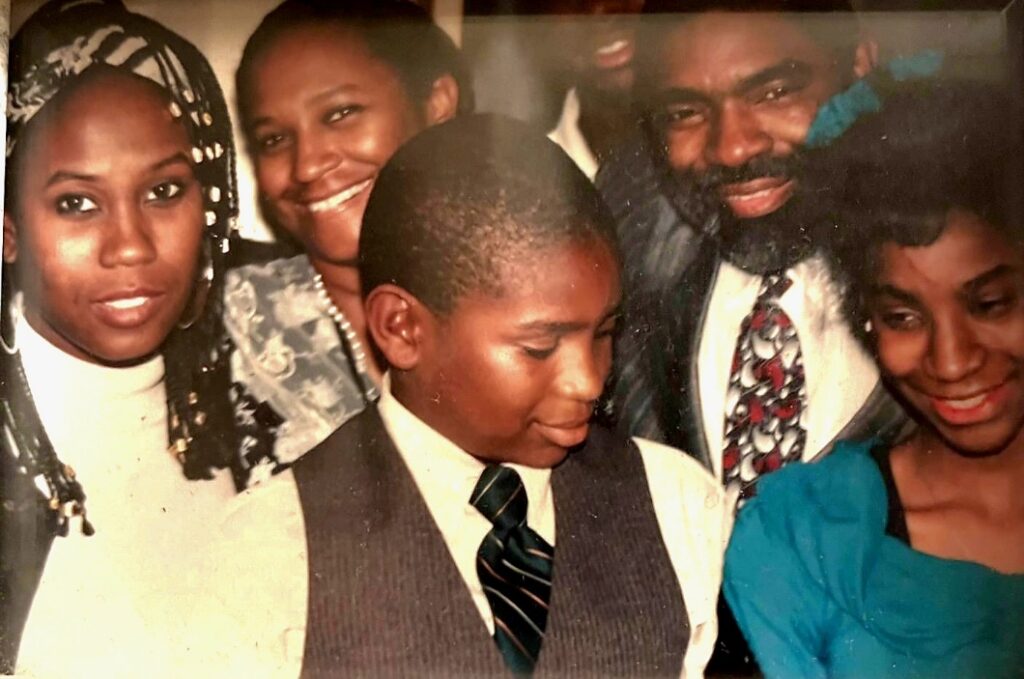

We sit for a moment honoring the passage of time flowing in the circuitry between us. The blood of our ancestors who survive in us testify. Mother of 4+2, Sidni, Loren Elizabeth, Rashida, Abdul Jaleel, Devon, Desiree. Grandmother of: Naimah, Yasmeen, Arralyn, Maizani, Devon, David. Great Grandmother: JahLee.

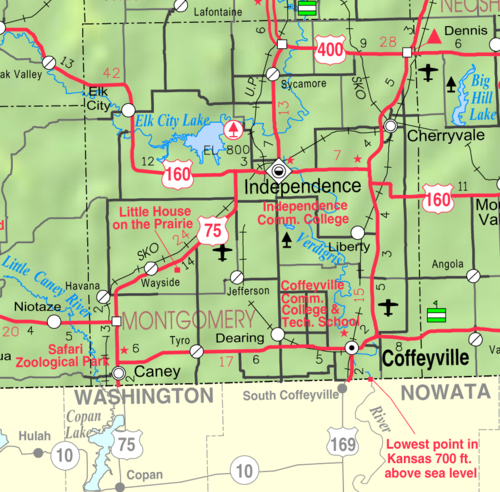

Her ancestors walk in her skin, step forward with feet wrapped in historic legacy. . . African and Indigenous, European too. Coffeyville, Kansas, is where her spirit stepped into flesh. A trading town: cows, bridges, train depot, cotton. . . Jim Crow, segregated elementary school, integrated high school. Papa, Iya Lola’s grandfather, though conceived in violence, was always known to be compassionate and caring. He founds Good Samaritan Club for widowed women and children. He also built the church where in the evening “Mama and Ms. Josie would be frying burgers,” Sister Lola says. “Papa and Mama fed the community during the Depression. Papa worked for the post office. A good job.”

We sort through the cast, Sister Lola and I. There are no understudies. Everyone plays herself or himself. The cameras are rolling. We use film, the expensive stuff. We cut no corners and only film in natural lighting like Julie Dash’s director of photography in Daughters of the Dust. This is where the tale ends. Both stories of exodus—movement of a people. Eventually Mama and Papa move to Los Angeles too.

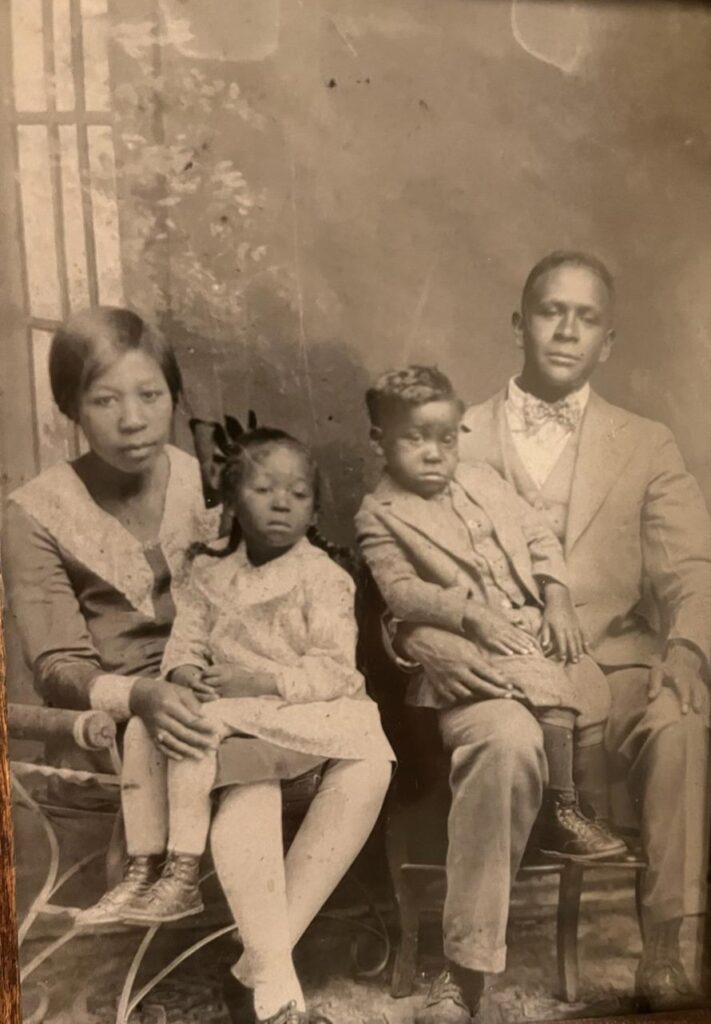

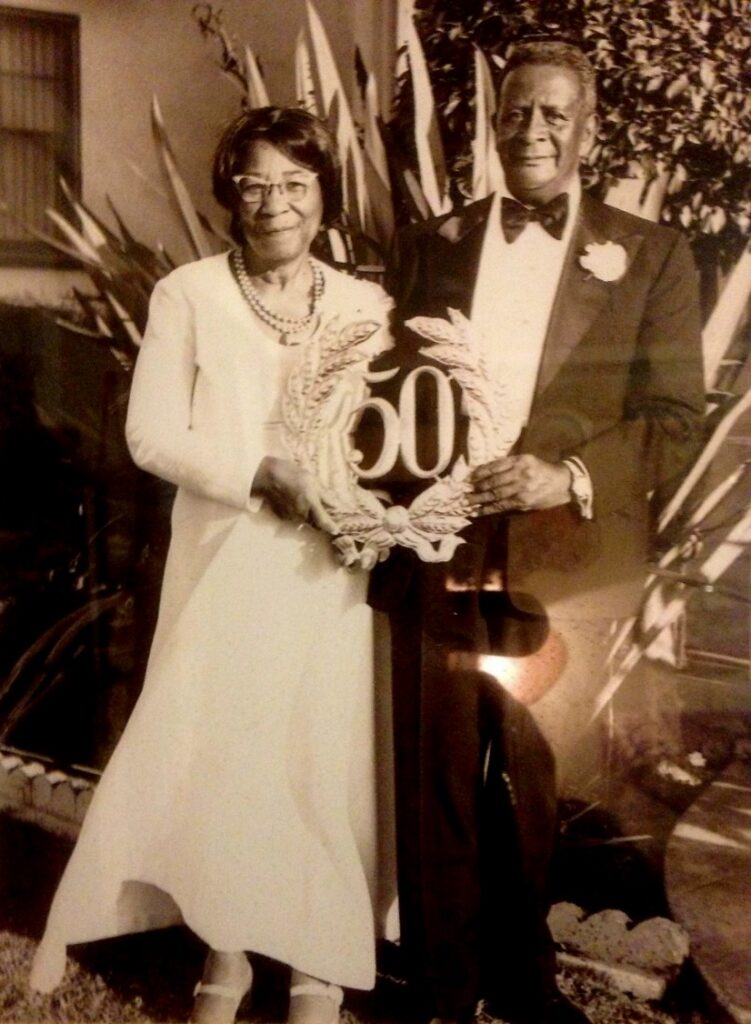

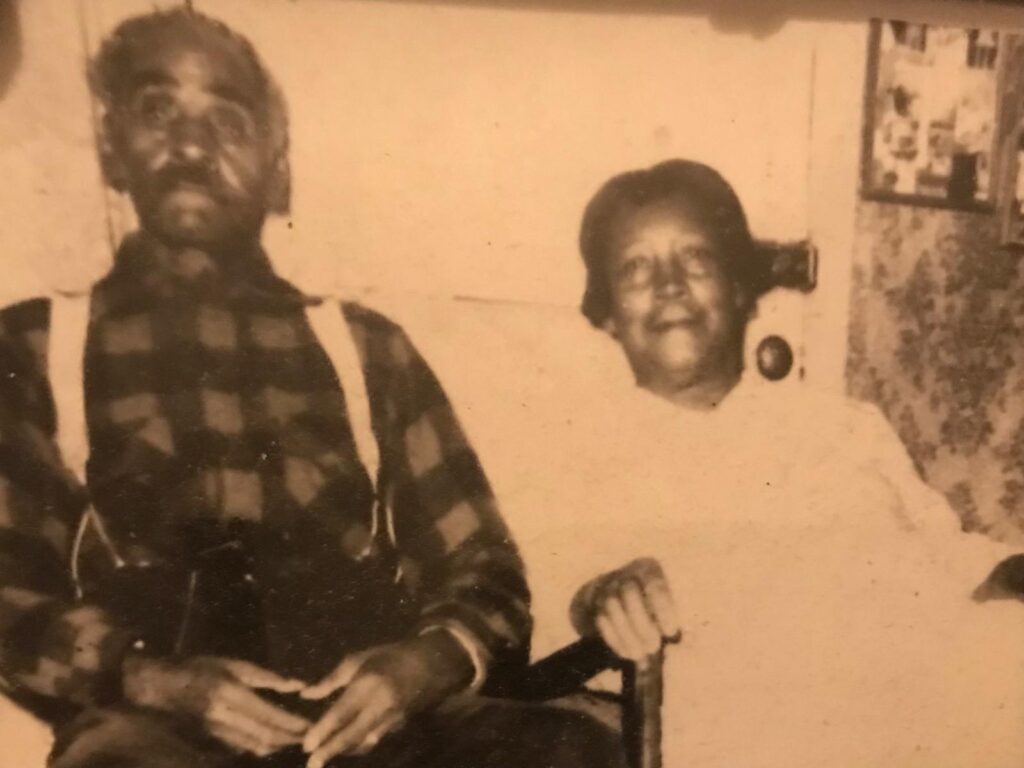

“I just remember this story, my grandmother told me when she first saw my grandfather. She said that she was looking out the window, standing in the doorway or something at the church– she and her sister, and she saw this new boy walking towards the church, and she says she told her sister, ‘I am going to get that little old boy,’ and she did. They were married when they were about 16, and they were married for 65 years.” Papa died in 1999 and in 2001 Mama joins him. They have five children; Lola Mae’s mama is the eldest.

“They went through, you know a lot of things together, but they really meant a lot, and still do, to the family, and to a lot of people in that community they were very instrumental in growing and nurturing, and being there for folks.

“Coffeyville, Kansas, is the town that I was born in, and grew up in like on the Kansas, Oklahoma border.” She says.

Say their names. . . Aṣe!

“Aunt Nemi, Papa’s mother’s aunt lived next door to Uncle Percy & Aunt Pat and their family. He was my grandmother/Mama’s brother. Aunt Velma and Mr. Hunt/Mama’s eldest sister lived across the street from them, in back of us, across the alley. Ross and Delia Lyle, Mama’s parents, my great grandparents (pictured below) lived across the street from us. They were the ones everyone was coming to see all the time . . . just respect, sit on front porch . . . in front yard talking/visiting. . . . We lived right in the middle of the [thoroughfare]. There was like traffic back and forth, family all day long going to see Grandma and Grandpa and I tell you what, no matter how many times they went through—you better say ‘Hi!’”

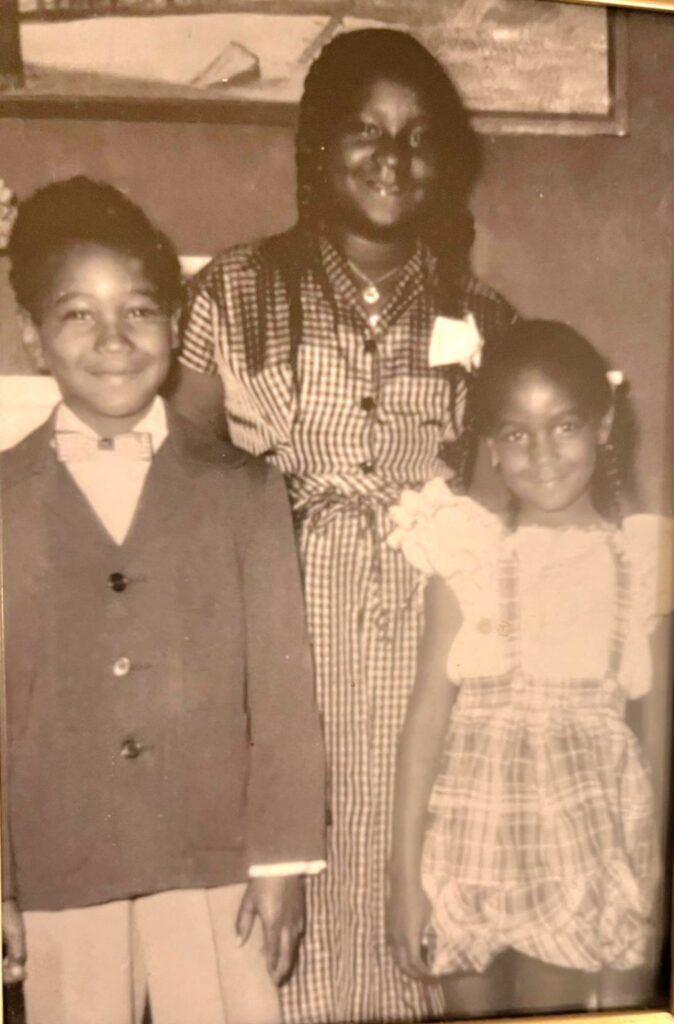

Lola is the third child with an older sister and brother, Patricia and Alfonzo Jr. and a younger sister, Rosalind. She says she was the spokesperson for the siblings. She was elected to represent the kids. We wonder what they did before she arrived.

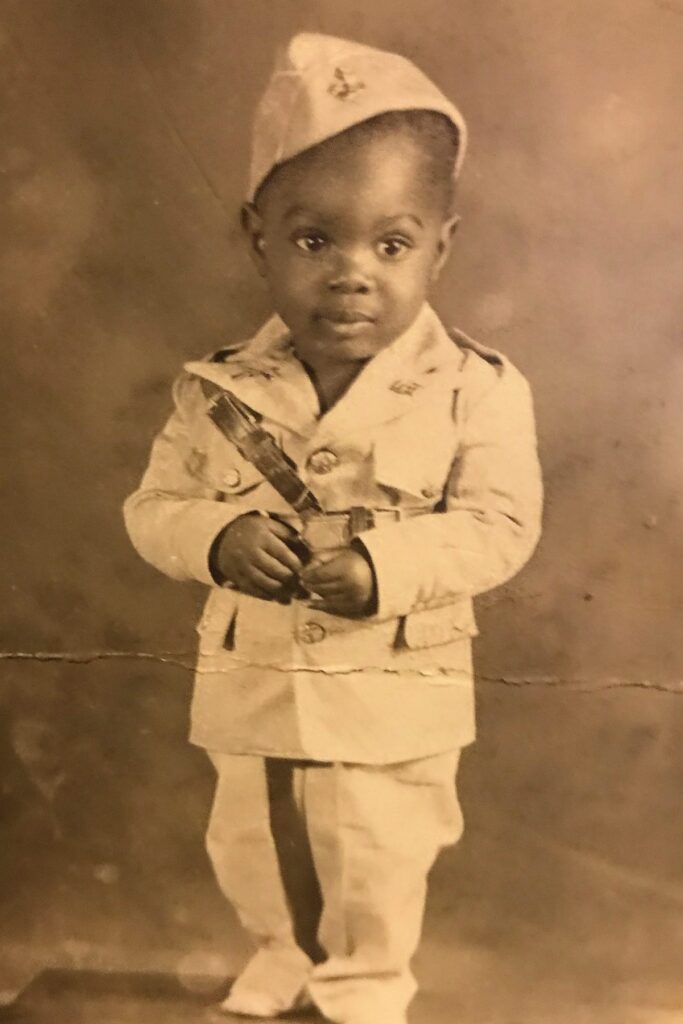

Her dad, Alfonzo Sr. is a WW2 veteran who worked on the Grand Coulee Dam in Washington State. It was a huge project unprecedented to date. That’s where her consciousness is born. She finds her many years later waiting. What belongs to us is never lost, Abby sings. Lola Mae knows inside this truth. Ahh, the magic she sees when distracted, when still feigning sleep. Clarity when it comes is wonderful.

Her father builds something grand, even as he unraveled. Her mom got away and saved herself and her children. She, girlchild is able to reconcile with her father. Lola says, he wept, the tangle unraveled between them as forgiveness grew. He was angry and bitter, and the children were just there, like the bed they hid under.

Lola Mae says after she’d left Coffeyville to visit an auntie, when she went back home she met her new family. Mom had moved on.

Life’s like that.

The land here is strange, Lola always felt. She looks up “[h]ow often at night, when the heavens are bright

With the light of glittering stars,

[and] stood . . . amazed and asked as [she] gazed

If their glory exceeds this of ours.”

II

Her tuning fork points West and at 17, Lola Mae hops on a Greyhound bus to Los Angeles where she stayed with one of her sheroes Aunt Shirley and babysat young cousins while finishing high school.

In 1966, LA was audacious, Black and proud. Grandmother Letha would take the bus back and forth ‘cross the country to help her divorced daughter, a nurse. So Lola Mae always knew out there was another world, bigger than the cows, dust and racist crackers at home.

Sister Lola, a prodigal daughter, felt her heritage here in LA. All around her Black people were standing up and shutting down oppressive systems. In her late teens then, life was exciting. Lola took courses at the community college, went on dates, got married and became a mother.

The young mother continued to conjure and stir her pots, following the magic in her heart. Spirit spoke to her often and she listened well. Trading in cosmic marketplaces for better lives for herself and her daughter Sidni, she left her marriage.

She had this agreement with a soul mate, an appointment with him, arranged by ancestors, heavenly beings before she arrived. She kept looking, asking for directions. . . . The first marriage ended in tragedy. She lost baby Loren at nine months. No more, the young mother decided, no more. I will stay home with my children. And she did. Tragedy is. . . Life lessons one survives.

LA was not to be her permanent landing place, just a spot to refuel, change the crew and sail off.

She kept keys in her back pocket– "California I love you . . . the greatest state of all. I love you winter, summer, spring and fall. I love your fertile valleys, your dear mountains I adore. I love your grand old ocean and I love your rugged shore." "I love you, Land of Sunshine. Half your beauties are untold. I loved you in youth and I love you [now that] I'm old. Queen Califia grinned as she waved at Lola Mae. She'll be back, she whispered . . . I know child, I know she sighed as her girl Lola sailed away.

III

Washington state is where Lola Mae fine-tuned her wombfulness.

Conceived in Washington, yet born in Coffeyville, Lola Mae felt at home here. No one could run her away, and the subtle microaggressions multiplied did not stifle her children nor her family’s growth.

MB Hanif, her soul mate, broadened his creative palate to include film and music, as the two parents of a blended family started organizations and hosted plays and other cultural events at their children’s schools.

These Black people were not going anywhere. They claimed agency– sovereignty and place. They taught their children they belonged because they did. Their mother’s song was their song too, a song of freedom, safety, belonging.

"This is my country; God gave it to me; I will protect it, ever keep it free. Small towns and cities rest here in the sun, Filled with laughter, 'Thy will be done.'" "[. . .] There's peace you feel and understand In this, our own beloved land. We greet the day with head held high, And forward ever is our cry. We'll happy ever be As [a] people always free. For you and me a destiny; [America] my home.

Yes, this land was made for you and me; Lola Mae skipped cut glass (cutlass) along the banks of a dam her father built. If it’s a girl, name her after me, her Grandmother Lola Carroll told her mom.

And so it be.

After 8 years, Sister Lola says, it was time to move again from Bellevue, Washington, back to the City of Angels briefly then Oakland called.

IV

Oakland was a place Sister Lola always felt an affinity. Kids visiting kin during Coffeyville summers spoke of a chocolate city, Oaktown. And then there she was in 1994. Black Power her magic carpet and Oakland certainly had a lot of that.

Her daughter Sidni called her mother here as she left for Malawi; then academic pursuits at San Francisco State University (SFSU) called Sister Lola’s name. There she got an undergraduate degree in Africana Studies and Health. Jaleel, her son, was in high school. Why not parley her experience into an academic package? She thought.

Sister Lola only took classes that interested her and so her feet led her after graduation to the University of Creation Spirituality where she got her master’s degree. She worked as a consultant, social worker and mediator. Called often to facilitate groups with alcoholic women, Sister Lola ended up founding Sacred Space Spiritual Support Group. She convened this healing space for 14 years. Hosting wellness talks with special guests, field trips and workshops.

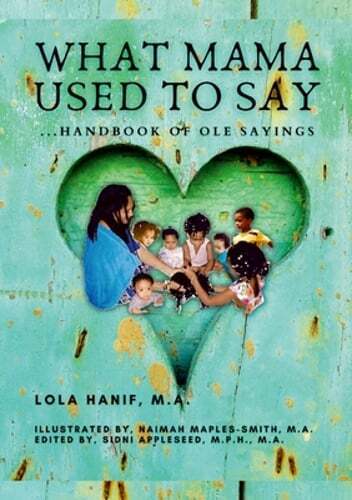

Now Sister Lola is writing. Her first book, What Mama Used to Say . . . Handbook of Ole Sayings just came out last year (2022) and is in its second printing.

She is writing a Memoir about her cosmic agreement with her husband, MB Hanif.

Sister Lola says throughout her life this saying has guided her flight and cushioned her landings “[a] heap see what a mighty few know” (33).

V

Though she sailed along the Nile Valley and visited the Pyramids, America is her home. Her great grandfather got to Oklahoma too late to claim his land, they say. The Trail of Tears story narrated by James Earl Jones speaks her family’s story too.

She’d watch her Great Grandfather fuss at reports on the TV. “Lies. Lies,” he’d say.

Cherokee on the Slaughter side. Choctaw on the Carroll side. This is her home now.

Colonel James A. Coffey (1827-1879) who was with John Brown and James H. Lane “in the capture of Washington Creek Fort and at the engagement of Lecompton [. . .]” to keep Kansas a free state, opened a trading post on rich Indian land. Chief Black Dog with his Osage people lived here first. 300 pounds, blind in his left eye, at 7 feet, he towered over the white man. By the time the iron bridge was built, 3 railways plowed through town, factories went up, industries like brick masonry were developed, the original people seemed to have vanished . . . but they were there in Sister Lola’s neighborhood. They live in the blood.

VI

Every day is a reawakening Sister Lola says. “I remember a lot of stories, yet you make your own path.”

“[A] heap see what a mighty few know. So many people judge what they don’t know.” What you know will carry you through.

“What if I’d listened to that girlfriend who told me not to marry a musician, especially a saxophone player?”

“We’d talk for hours. Hanif could see me. When I’d walk him to the door and we both touched the doorknob sparks would fly between us.”

Magnetic.

“When I looked at him I saw a long dark tunnel with light. . .we weren’t a traditional couple. However, our agreement was I stayed home with our children and he could play his music.”

“We’ve been married almost 50 years. I like him too.”

Everyone don’t get it. Everyone can’t come. Everyone has a different purpose.

“[A] heap see what a mighty few know.”

It’s a calling. “Trials and tribulations. It’s better to bend than break.” Mama would say. “Step back and let the train go by.” There is always another one coming (41).

Sister Lola hasn’t missed any cues or curtain calls from 17 to now. For more, contact her agent at 1-800-I-SIRIUS